Design federal support for innovation to serve a clear public purpose

David Watters is a former assistant deputy minister for economic development and corporate finance in the Department of Finance, the founder and former CEO of the Global Advantage Consulting Group, and the founder and current president of the not-for-profit Institute for Collaborative Innovation.

David Watters is a former assistant deputy minister for economic development and corporate finance in the Department of Finance, the founder and former CEO of the Global Advantage Consulting Group, and the founder and current president of the not-for-profit Institute for Collaborative Innovation.

This op-ed first appeared here in The Hill Times.

The idea of innovation can be difficult to understand. Fortunately, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development has been studying and measuring innovation for several decades and has fixed on a common definition, which OECD countries use, including Canada.

“An innovation is a new or improved product or process (or combination thereof) that differs significantly from the unit’s previous products or processes and that has been made available to potential users (product) or brought into use by the unit (process),” according to the OECD.

There are several important public policy consequences that follow from this definition.

First, while products are defined as both “goods” and “services,” most federal innovation support has focused on innovating new manufactured “goods” that are patentable and based on research from the natural sciences (physics, chemistry, biology, etc.).

But Canada’s manufacturing sector is only nine percent of the total of the economy, while the service sector is now about 75 percent, according to Statistics Canada.

This is important because the Scientific Research and Experimental Development program, Canada’s largest innovation support program, providing $4.5 billion annually in tax credits targets R&D in the natural sciences and in engineering to produce new goods – and explicitly excludes research in the “social sciences.”

However, these social sciences disciplines, including economics, psychology, sociology, education, law, and management, are fundamental areas of research to grow our service sector. No wonder Canada has a productivity problem.

Second, note that the term “unit” to describe the people who innovate refers very broadly to all stakeholders in society. This is important because federal innovation policy has focused almost exclusively on the activity of “firms.”

But as the OECD makes clear, any public or private organization, and any household or individual can innovate. As a result, innovation should not be limited just to industries – but rather it is everyone’s opportunity, whether in governments, small businesses, hospitals, non-profits, communities or individuals.

In summary, innovation is simply about trying to improve the performance of any human activity, and, collectively, innovation is the history of our civilization.

Third, to be considered an innovation, “it needs to be implemented.” This means it needs to be used broadly in order to generate value.

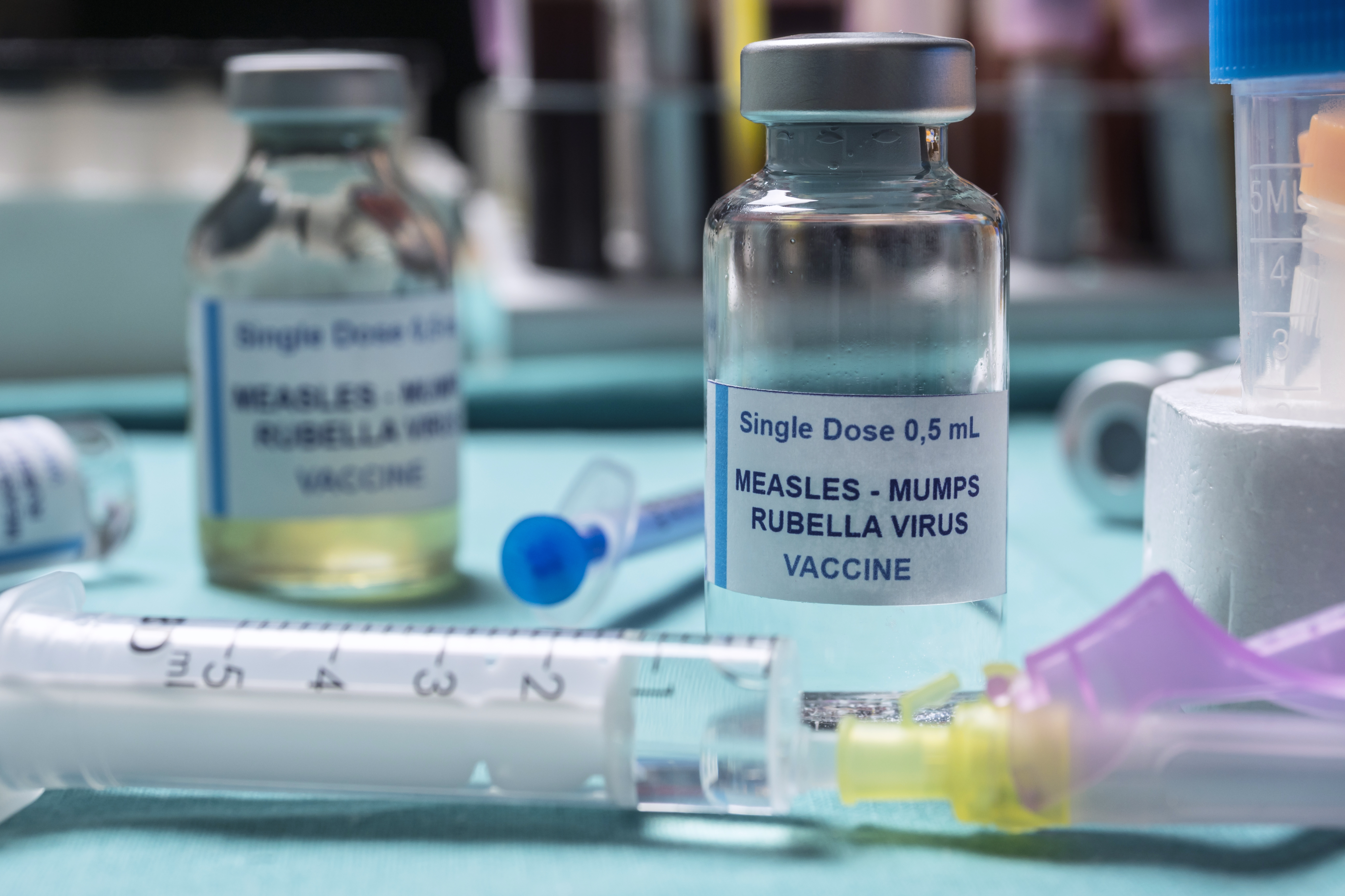

For example, the value of the new COVID-19 vaccines depended on their being used – by vaccinating billions of people to produce health benefits. But how can governments increase the widespread use of important new goods or services?

Expanding innovation use and diffusion

Here are three steps to expand innovation use and diffusion:

- Increase public knowledge of the benefits produced by an important new good or service.

- Increase accessibility and affordability of the new good or service.

- Manage and regulate production and use of the new good or service to protect the public interest.

Fourth, innovation is not limited to creating a good, service, or process that is new to the world. To improve performance and value, an innovation only has to be new to the organization, household or individual.

So the adoption of a new technology by Firm A, even if it was created by Firm B, is still regarded as an innovation. And this makes sense because if I, as Firm A, buy a computer system, software or AI app made by another firm, it will still be new to my operations, and will likely improve my performance and productivity.

Canadian governments have focused too much on subsidizing technology “creation” by a few firms, instead of widespread technology “adoption” by all firms. To improve Canadian productivity, we need to pivot and support widespread technology adoption.

In summary, innovative goods and services can result in broad public benefits if widely diffused throughout a society. These public benefits go well beyond the benefits that accrue to the few private-sector firms that create these technologies.

Unfortunately, federal innovation policy and program support has focused primarily on subsidizing the producers of new technologies, and not enough on supporting the widespread adoption of new technologies.

Therefore, since public money is being used by governments to support innovation, its effectiveness should be measured by the public benefits that it provides to citizens, in order to improve their quality of life.

That is why all federal support for innovation should be designed to serve a clear public purpose.

R$

| Organizations: | |

| People: | |

| Topics: |

Events For Leaders in

Science, Tech, Innovation, and Policy

Discuss and learn from those in the know at our virtual and in-person events.

See Upcoming Events

You have 0 free articles remaining.

Don't miss out - start your free trial today.

Start your FREE trial Already a member? Log in

By using this website, you agree to our use of cookies. We use cookies to provide you with a great experience and to help our website run effectively in accordance with our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.