Survey: Canadian universities are increasingly cutting fossil fuels from their investment portfolios

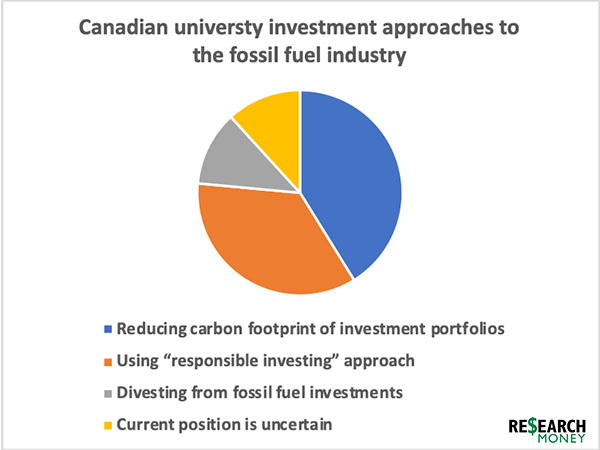

Some of Canada’s largest universities are significantly reducing the carbon footprint across all industrial sectors in their investment portfolios, while many schools are using a “responsible investing” approach, a Research Money survey shows.

Concerns about greenhouse gas emissions and climate change are motivating many post-secondary institutions to change their portfolios, but the financial risk of holding plummeting carbon-intensive investments also is driving the shift.

Less than a handful of Canadian universities have committed to fully divesting from their fossil fuel holdings, although pressure on others to join the trend is increasing, due to accelerating divestment internationally by universities, other public institutions and the private sector, say academics and investment managers.

“There has always been a moral argument in favour of divestment. But it’s the financial argument that’s fueling the rapid amount of divestment decisions we’re seeing now,” James Rowe, associate professor of environment studies at the University of Victoria, told Research Money. Rowe has examined divestment by Canadian universities and co-authored a report on the Canada Pension Plan and divestment.

"We’ve done better than we would have had we continued to invest in fossil fuels.” - Alison Blair, associate vice-president of finance at Simon Fraser University

In March, share prices of many Canadian oil and gas companies fell by 40% to 70%, due to the COVID-19 pandemic and an oil price war between Saudi Arabia and Russia. Alberta Premier Jason Kenney has warned that Alberta’s oil industry is on “life support.”

In the Research Money survey, the University of Toronto and Université Laval responded that they’ve set targets to reduce the carbon footprint in their investment portfolios by 40% to 50% by 2030.

McGill University has rejected calls for divestment three times in seven years. Instead, the university’s new investment framework will cut the carbon footprint in McGill’s portfolio, with de-carbonization targets and timelines to be presented in April to the board of governors.

But there are problems with using the carbon footprint reduction, or “de-carbonization” approach, rather than divestment, says Gregory Mikkelson, who resigned his tenured position as an environmental science professor at McGill in January over the university’s refusal to divest in fossil fuels and what he calls the board of governors’ “anti-democratic nature.“

De-carbonization and the method for calculating the carbon footprint exclude all greenhouse gas emissions that occur after the sale of a company’s product, he said in an email to Research Money. “So-called de-carbonization in effect aims to make fossil fuel corporations more efficient at extracting their product from the ground,” Mikkelson says. “Divestment aims to keep most fossil fuel in the ground and thus prevent disastrous levels of global warming."

Rowe agrees, saying the de-carbonization approach allows universities to remain invested in fossil fuel companies and doesn’t address the moral and financial risks of such investment given the climate emergency.

SEE THE FULL SURVEY HERE.

Nik Dworek, a spokesperson for Divest McGill, says the student-led campaign will keep pressuring the university to fully divest. “Instead of actually taking action on climate change to benefit our futures, investing in fossil fuel companies is not really going in the right direction,” he said in an interview.

However, several universities that responded to Research Money's survey — including Simon Fraser University, University of Toronto, and Université Laval — argue that de-carbonization will reduce more carbon overall than divesting only from fossil fuels. The University of Ottawa, Queen’s University, and McMaster University are also using the de-carbonization approach.

Université Laval “recognizes that it is simplistic to allocate responsibility for greenhouse gas emissions exclusively to fossil fuel producers,” Simon La Terreur-Picard, a media advisor at Laval, said in an email to Research Money. “Therefore, adopting a broader scope encompassing the carbon emissions of all sectors is more rigorous, logical and scientific.”

Simon Fraser University has already surpassed its target to reduce the carbon footprint by 45% by 2025, although it still has about $10 million, or 1%, of its portfolio invested in fossil fuel companies, Alison Blair, Simon Fraser’s associate vice-president, finance, said in an interview. “We’ve already reduced the footprint of the portfolio by more than 50%,” she says. “If we had divested of all fossil fuels and only done that, and not reduced carbon footprint overall, we would have had a higher carbon footprint today.”

Blair says when SFU started measuring the carbon footprint of its portfolio in 2016, university officials were worried about earning lower returns. “We’ve actually done really well,” she says. “Given the way that oil has performed, I know we’ve done better than we would have had we continued to invest in fossil fuels.”

Move to divest is “accelerating”

R$ emailed a brief, informal survey to 17 Canadian universities, including all members of the U15 group of research universities, and gave them three weeks to respond. (See table for survey results). Eleven universities responded, although several returned prepared statements rather than answering the survey questions.

The fossil fuel holdings across all the universities’ portfolios (endowment, trust and investment funds) represented a small percentage of each portfolio’s assets, ranging from 5.7% at Concordia University to 1% at Simon Fraser University, based on R$’s survey. The market value of these fossil fuel investments, as reported by the universities, ranged from $66 million at Queen’s University to approximately $5 million at Université Laval.

As for universities divesting specifically from the fossil fuels industry, the UQAM Foundation, the financial arm of the Université du Quebec à Montreal, has fully divested the university’s approximately $3 million. Concordia University in Montreal has committed to end investment in the coal, oil and gas sectors by 2025.

The University of British Columbia’s board of governors in December supported full divestment of fossil fuel holdings in the university’s investment portfolios “as soon as possible.”

UBC’s decision was directly influenced by the University of California’s decision last September, based on the financial risk, to divest its $13.4-billion endowment fund and $70-billion pension fund — the largest-ever divestment by a public university, Rowe says. “Now that UBC has decided to divest, that’s putting pressure on universities in Canada. So I think we’re going to see it more and more.”

The divestment movement “is definitely accelerating. We’re seeing more universities starting to move towards divestment,” says Wayne Wachell, CEO, chief investment officer and founding partner at Genus Capital Management in Vancouver.

Wachell is known as Canada’s “father of fossil-free investing” because his company offered the first suite of fossil fuel-free funds in the country. Genus Capital manages about $1.6 billion in assets. Its fossil fuel free, sustainable investments have grown from about $80 million seven years ago to $600 million today, he says. “It has been the fastest-growing part of our business, growing at about 20% per year.”

Worldwide, more than 1,110 institutions with more than $11 trillion in assets under management have committed to divest from fossil fuels, according to CleanTechnia’s 2019 Divestment Year in Review report. Assets committed to divestment have increased from $52 billion in 2014 to over $11 trillion today.

Some universities using “responsible investing” approach

Université de Montreal told Research Money it is not divesting but is considering environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors in selecting and managing investment portfolios. Dalhousie University, University of Alberta, the University of Saskatchewan, the University of Waterloo, and Western University are all taking a similar ESG-focused approach.

Rowe, however, says 10 to 15 years of shareholder engagement and activism on ESG factors with fossil fuel companies hasn’t produced meaningful behavioural change in the industry. “They are not actively seeking to make a transition [to clean energy], so we need a different approach.” Divestment, he adds, is a more significant market signal.

SEE THE FULL SURVEY HERE.

Rachel Bensler, a student at the University of New Brunswick and leader of the Fossil-Free UNB Campaign, wrote that universities are “greenwashing . . . by arguing that the companies they invest in are constantly improving, or by stating that low-carbon initiatives are adequate, or by claiming that environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors are being taken into account without actual evidence of what this looks like.”

In response to the divestment movement, The Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers (CAPP) says global demand for oil is forecast to continue to grow at a near-record pace, particularly in energy-poor regions. “Canadian oil and natural gas is produced in one of the most highly regulated jurisdictions globally and is among the most sustainably produced energy sources in the world, and we should be offering this supply to the world. We would encourage groups who are redefining their investment portfolios to consider that an investment in Canadian energy is a sustainable choice,” Jay Averill, CAPP’s manager of media relations said in an email.

But well-known financial analyst Jim Cramer, host of “Mad Money” on CNBC, said in January that oil and other fossil fuel stocks are in the “death knell phase . . . We’re starting to see divestment all over the world.” BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager, said in February that one of its fast-growing green-oriented funds would stop investment in companies that get revenue from Alberta’s oil sands.

Blair at Simon Fraser University says: “I don’t see oil as being a good investment anymore for the future. I think it’s on the way out and the transition to clean energy will continue and take over.”

“Yesterday’s tobacco is today’s fossil fuel,” says Genus Capital’s Wachell, who predicts fossil fuel companies will increasingly be shunned by investors. “The tides are shifting in terms of how we view fossil fuel companies and their contribution to our escalating global climate crisis.”

R$

Events For Leaders in

Science, Tech, Innovation, and Policy

Discuss and learn from those in the know at our virtual and in-person events.

See Upcoming Events

You have 0 free articles remaining.

Don't miss out - start your free trial today.

Start your FREE trial Already a member? Log in

By using this website, you agree to our use of cookies. We use cookies to provide you with a great experience and to help our website run effectively in accordance with our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.