Productivity decline and the role of natural capital

Peter Josty is Executive Director of The Centre for Innovation Studies, based in Calgary.

Peter Josty is Executive Director of The Centre for Innovation Studies, based in Calgary.

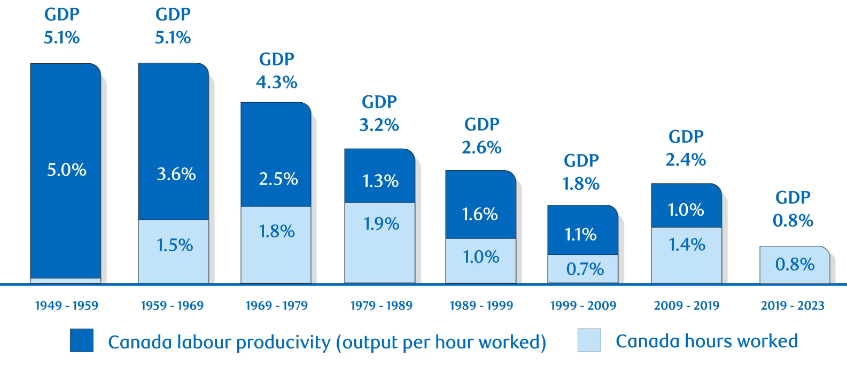

Growth and productivity have been declining in Canada since the 1950s. The graphic below, from the Royal Bank, illustrates this.

Source: Royal Bank

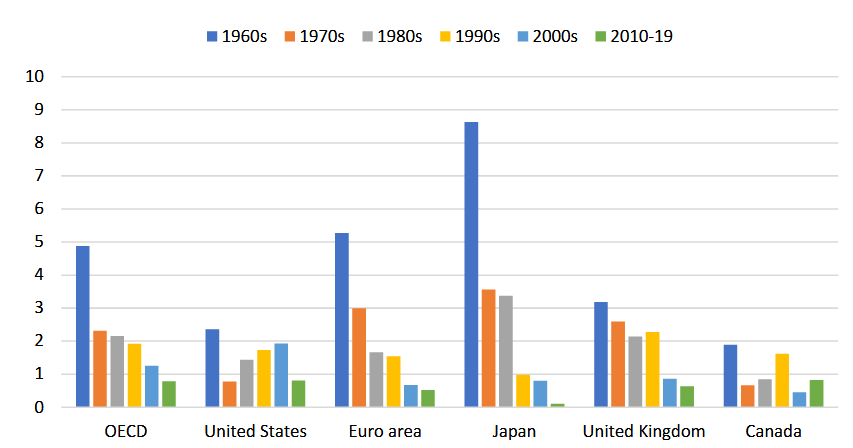

However, declining productivity is not just a Canadian problem; it has occurred in all the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries.

The graphic below shows the average growth rate of labour productivity for the combined OECD countries and selected countries, since the 1960s. While the pattern is slightly different for each country the overall declining trend is clear.

Source: OECD

Looking to the future does not appear promising. The OECD has projected an average per capita GDP growth rate for all the OECD countries of 1.1 percent annually over the period 2030-2060.

Canada has the lowest growth rate of all OECD countries, at 0.8 percent annually.

Why has productivity been declining?

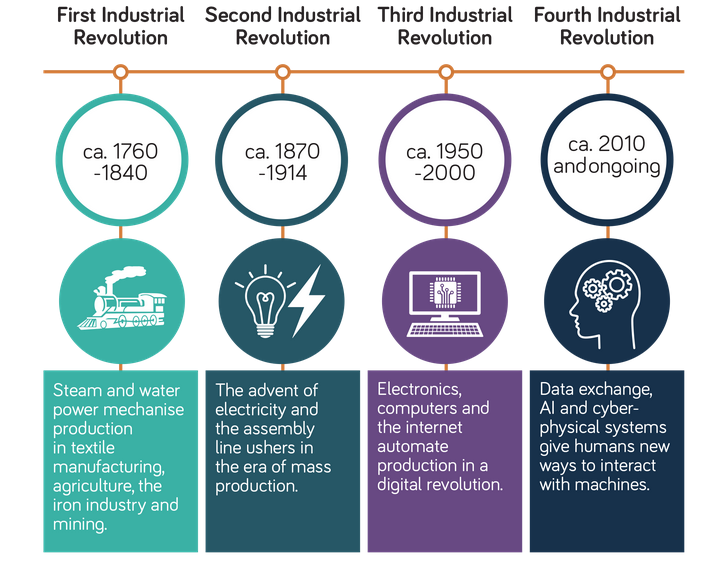

There is no consensus about the reasons for the decline. The most widely accepted explanation is that the decline is due to the decline in technological innovation as the Third Industrial Revolution matures. The graphic below illustrates this.

Source: Neos Networks

However, this explanation is not really consistent with the very low growth projected for the future by the OECD.

That is supposed to be the time the Fourth Industrial Revolution – based on artificial intelligence, digitization, synthetic biology, and robotics – kicks in and produces robust growth.

One overly optimistic version of this view is The Techno-Optimist Manifesto written by Marc Andreessen, a leading Silicon Valley venture capitalist. This sees technological progress driving ever increasing prosperity and social development in the future.

A similar view is expressed by Klaus Schwab in his book The Fourth Industrial Revolution, where he writes: “I am convinced that the fourth industrial revolution will be every bit as impactful and historically important as the previous three.”

The techno-optimist view is convincingly debunked by Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson, winners of the 2024 Nobel Prize in economics in their recent book, Power and Progress: Our Thousand-Year Struggle Over Technology & Prosperity.

As they point out: “There is nothing in the last thousand years of history to suggest the presence of an automatic mechanism that ensures gains for ordinary working people when technology improves. On the contrary, there are plenty of episodes in which technological breakthroughs were associated with no improvement – or even significant deterioration – in working conditions and living standards for most people.”

Nevertheless, it would be surprising if all the new technologies didn’t drive more growth and productivity gains than described in the OECD forecast.

An alternative explanation for declining productivity

A recent paper by independent economist Christina Caron presents an intriguing alternative explanation of the decline in productivity that has ominous implications for the future. She points out that the pervasive and persistent nature of the decline signals that factors of global scope and extended duration are likely implicated.

The alternative explanation is that erosion of natural capital (including depletion of natural resources, damage to ecosystems and loss of climate stability) has been occurring on a sufficiently large scale globally that it has become a significant driver of declining global productivity growth.

The notion of natural capital has slowly entered the mainstream after its first description in the 1970’s. The OECD notes that traditional measures of multi-factor productivity growth generally do not recognize natural capital as inputs into the production process.

They define natural capital as "natural assets in their role of providing natural resource inputs and environmental services for economic production" and is "generally considered to comprise three principal categories: natural resources stocks, land, and ecosystems."

The field of natural capital accounting is developing to quantify the impact of natural capital on economic growth and productivity.

Statistics Canada is part of a working group together with Australia and the U.S. to align environmental and economic data into national environmental-economic statistics.

The World Bank estimates that the global economy could lose US$2.7 trillion by 2030 (compared to business as usual) if certain ecosystem services collapse (such as pollination, carbon sequestration and storage fisheries, and timber provision).

The OECD says that between 1992 and 2014, natural capital stocks per capita declined by nearly 40 percent.

How natural capital impacts economic growth

Caron’s paper points out a number of mechanisms for how natural capital impacts economic growth and productivity. She points out that this is most evident in the resource sector, where agriculture relies on arable soil, seeds, rain and a stable climate; fisheries depend on fish populations; mining depends on mineral deposits (including oil and gas).

Manufacturing uses plenty of natural resources such as wood and concrete. The first and second Industrial Revolution was almost entirely powered by fossil fuels.

Evidence indicates that at some point in the second half of the 20th century the rapidly expanding scale of human impacts on the natural environment began to outstrip the capacity of natural systems for regeneration.

There are several transmission channels for how natural capital impacts productivity:

- GDP decline: caused by wildfires, smoke or weather incidents.

- Labour intensity: extreme heat or fires reduce labour productivity.

- Physical capital: Damage and destruction of physical capital (e.g., Jasper and Fort McMurray wildfires)

- Human capital: Illness, disability, and premature mortality caused by pollution.

- Obsolescence: Unanticipated environmental change reduces the productive lifetimes of investments.

- Reallocation effects: Declining natural capital can cause changes in the relative productivity of firms, resulting in sectoral reallocation effects.

Conclusion

There is no doubt that productivity has declined in most countries since the 1950s. There isn’t a consensus on the reasons for this, but a prominent view is that it is due to the decline in technological innovation as the Third Industrial Revolution matures.

A novel and intriguing alternative explanation is that the decline is due to degradation of the world’s natural capital.

Canada can preserve its natural capital by undertaking measures such as restoring wetlands, protecting urban tree canopies, conserving grasslands, protecting watersheds, and investing in sustainable infrastructure.

For future growth, there appear to be two main factors involved – the growth arising from the Fourth Industrial Revolution, offset by declines caused by economic degradation. Time will tell which will prevail.

R$

| Organizations: | |

| People: | |

| Topics: |

Events For Leaders in

Science, Tech, Innovation, and Policy

Discuss and learn from those in the know at our virtual and in-person events.

See Upcoming Events

You have 0 free articles remaining.

Don't miss out - start your free trial today.

Start your FREE trial Already a member? Log in

By using this website, you agree to our use of cookies. We use cookies to provide you with a great experience and to help our website run effectively in accordance with our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.

.jpg)