Concentrating on competition

It is widely accepted that competition has many benefits — lower prices, higher quality goods and services, more innovation and variety, and higher productivity. The topic is top of mind because of the ongoing Rogers/Shaw takeover saga.

So how is Canada doing? Let’s look at a couple of Canadian examples.

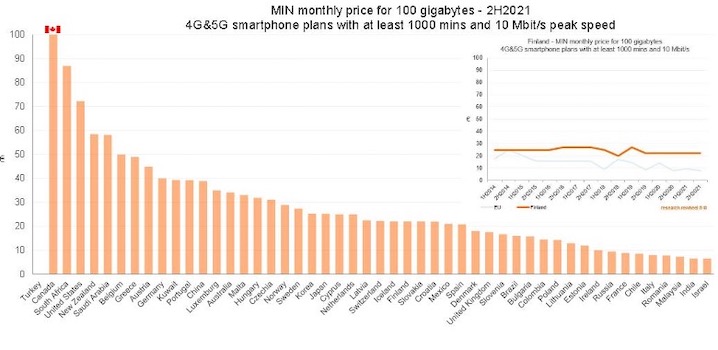

- Mobile phone costs. The graph below, from a Finnish company, shows monthly prices for a standardized cell phone in a number of countries.

Canada has a very concentrated cell phone market with only three national providers (Rogers, Bell and Telus), plus several smaller regional providers. A Canadian Radio-Television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) review found the prices charged by those three providers and their profits are higher than in other countries. However industry concentration is clearly not the whole story, as Australia has an even more concentrated market than Canada, and their prices are only a third of those in Canada. Australia also faces the same low population density issues as Canada.

- According to a 2019 (i.e. pre-COVID) study, prices for flights in Canada are among the highest in the world. Canada ranks 65 out of 80 countries for the cost of domestic flights, ranked lowest to highest. When comparing the price of flights in Canada to the United States, Canadians pay on average 108 percent more for tickets. The average cost per 100 km flown in Canada came in at $23.90, compared to that of United States coming in at $11.50 per 100 km. The study gives two reason for the high process:

- There is very little competition in Canada, with only two major airlines.

- Canada’s landing fees are among the highest in the world.

More concentrated markets give suppliers market power — the ability to raise prices above the level that would be seen in a more competitive market.

How to measure industry concentration.

In Canada the Competition Bureau uses a set of qualitative factors, but includes a market share of the four largest firms as one metric. If the four largest firms have a greater than 65 percent market share, that is considered concentrated. The four largest mobile phone companies have a 95 percent market share, and the four largest airlines an 86 percent market share, both indicative of very concentrated markets.

In the U.S., the U.S. Department of Justice uses the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index, (HHI) to evaluate competition arising from mergers and acquisitions. The HHI is the sum of the squares of the percentage of market shares of companies in a given market. A HHI number below 1,500 is considered unconcentrated, between 1,500 and 2,500 moderately concentrated, and greater than 2,500 is considered to be a concentrated market. The HHI for the mobile phone market in Canada is about 2,680, or highly concentrated, and the HHI for domestic airlines is about 3,316, even more concentrated.

However there are several thorny problems with measuring industry concentration: defining the market and defining the product.

Defining the market. Let’s look at airlines as an example. Although Canada as a whole is served by two main airlines, they do not compete equally across the country. The latest development is WestJet’s plans to concentrate more on western Canada, and Air Canada’s focus on eastern Canada. Newcomers — such as Porter, Flair, Sunwing and Lynx — have a short term effect, but are usually eventually acquired by one of the major airlines. For example, WestJet announced its intention to acquire Sunwing. So the more narrowly you define the market, the more concentrated it gets.

Defining the product. Airlines provide a good example here as well. There is a big difference between first-class travel and economy travel, in terms of cost and convenience. So lumping them together as “airlines” isn’t helpful. Business travelers are about 12 percent of all passengers, but contribute disproportionately to airlines profits.

The remedy.

Broadly speaking there are two approaches to obtaining the benefits of competition in highly concentrated markets — regulation and anti-trust legislation.

Regulation. For highly concentrated markets, such as airlines and mobile phones, there is often an agency charged with regulating the industry to provide consumer protection. For airlines in Canada, it would be the Canadian Transportation Agency, which oversees passenger rights regime. There has been much published about the effectiveness (or lack thereof) of this agency, and recently appointed CRTC Chair Vicky Eatrides almost immediately issued a statement outlining a renewed approach to telecommunications policy. For any effective regulator, policy should include reasonable solutions for consumer protection in highly concentrated markets.

Legislation. In Canada this is the Competition Act, which is administered and enforced by the Competition Bureau. The Act, and the Bureau, were designed before the rise of the Internet and the digital economy. They need to be updated to be effective, with a first round of changes in 2022, and there is a discussion paper circulating about possible additional changes.

Final word

There are many concentrated markets in Canada. Achieving the benefits of competition in these markets lies with better regulators and better anti-trust legislation. Let’s hope that the legislators - the CRTC and the Canadian Transportation Agency - can rise to the challenge. However mobile phones and airlines are only two of a great many concentrated markets in Canada.

R$

| Organizations: | |

| People: | |

| Topics: |

Events For Leaders in

Science, Tech, Innovation, and Policy

Discuss and learn from those in the know at our virtual and in-person events.

See Upcoming Events

You have 0 free articles remaining.

Don't miss out - start your free trial today.

Start your FREE trial Already a member? Log in

By using this website, you agree to our use of cookies. We use cookies to provide you with a great experience and to help our website run effectively in accordance with our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.