Canada ready to build its own world-class supercomputer but needs to couple it with an advanced technology program

Canada has the expertise now to build its own “top 10 in the world” supercomputer, says a Queen’s University scientist who has helped build the world’s largest supercomputers.

Canada has the expertise now to build its own “top 10 in the world” supercomputer, says a Queen’s University scientist who has helped build the world’s largest supercomputers.

But a made-in-Canada supercomputer needs to be coupled with an advanced technology program to train Canadians on the machine and to work with homegrown firms to supply the technology, said Ryan Grant (photo at right), associate professor of electrical and computer engineering and head of Queen’s Computing at Extreme Scale Advanced Research Laboratory.

His lab builds the software that makes the world’s largest computers work and is the largest group of experts on “exascale” systems (the world’s most powerful supercomputers) in Canada.

“We have the capability to be able to build a top-10 system today if we made the investments in the right way and we lean on some of the experience that we have in Canada,” Grant said in an interview with Research Money.

“If we just grow our existing talent base, we can grow something really special that will be top-world competitive,” he said.

The goal should be not only constructing a world-class made-in-Canada supercomputer, but building expertise and scaling up a domestic supercomputing industry that can export its trusted products internationally, Grant said.

“If you want to be in an industry, you’re either going to be a producer or a consumer,” he said. “I want to make sure that we have that supercomputer here in Canada so that we can be a net exporter of AI rather than an importer of AI.”

Without coupling a homegrown supercomputer with an advanced technology program, Canada will end up essentially “outsourcing production,” including the compute power required to build globally competitive AI foundational models and applications, Grant said.

The federal government, in Budget 2025, committed $925.6 million over five years "to boost domestic AI compute capacity, build public supercomputing infrastructure and accelerate public service adoption [of AI]." Ottawa is expected to issue a request for proposals early this year for a new supercomputer.

Grant said there are several proposals to build a supercomputer “out there in the wild right now that are pretty close to shovel-ready.”

Queen’s University has a proposal that’s “very shovel-ready,” he noted. That includes incubating the local talent required to build a supercomputer, particularly one that’s secure enough to enable academic-industry engagement on the system.

Queen’s proposal also includes making potential investments in future dual-use (civilian and military) technologies that can happen in a single supercomputing facility.

By the time the federal government issues its request for proposals, Queen’s hopes to have all its architectural drawings ready for its supercomputer, as well as its initial system design.

Queen’s proposal also includes recouping some of the initial investment from industry partners that will use the supercomputer, “so that it’s not coming back to the public purse,” Grant said.

“We think that’s a unique element of our particular proposal and it keeps it up to date. It also lets us incubate Canadian technologies faster and get them to larger scale faster.”

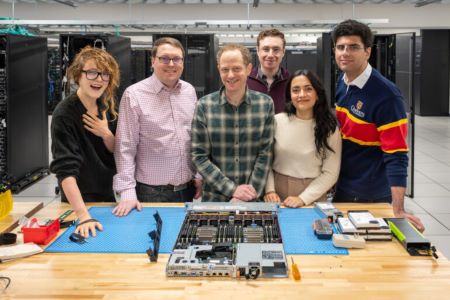

In December, Queen’s announced that it recruited Ian Karlin (centre in photo at right, with Ryan Grant and graduate students Brooke Henderson, Ethan Shama, Shaina Smith, Ethan Shama, and Ali Farazdaghi from Ryan's lab: Queen's University) to help build its supercomputer. Karlin’s arrival at Queen’s follows years of working on the leading edge of advanced computing, most recently as a principal engineer at chip giant NVIDIA.

In December, Queen’s announced that it recruited Ian Karlin (centre in photo at right, with Ryan Grant and graduate students Brooke Henderson, Ethan Shama, Shaina Smith, Ethan Shama, and Ali Farazdaghi from Ryan's lab: Queen's University) to help build its supercomputer. Karlin’s arrival at Queen’s follows years of working on the leading edge of advanced computing, most recently as a principal engineer at chip giant NVIDIA.

As a senior member of NVIDIA’s accelerated computing product group, he engaged with major laboratories across the United States, Japan, and Europe.

Karlin served as technical lead for two upcoming U.S. supercomputers and, before joining NVIDIA, served as principal high performance computing strategist at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California, where he led benchmarking and performance evaluation for El Capitan, currently the world’s most powerful supercomputer.

At Queen’s, Karlin, an assistant professor, will collaborate with Grant and his team at the Computing at Extreme Scale Advanced Research Laboratory.

Queen’s University and Bell partner to build a world-class supercomputer facility

Also in December, giant communications company Bell and Queen’s University signed a memorandum of understanding to build and operate a next-generation, world-class AI supercomputing facility.

This partnership will enhance Canada's AI capacity, drive domestic adoption of AI tools, and strengthen digital sovereignty, Bell said.

As a Canadian-owned and governed initiative, the new supercomputer will help safeguard sensitive data and intellectual property from foreign government ownership and oversight.

Bell will lead the design, construction, financing and maintenance of the turn-key building that will run on the company’s high-speed, low-latency fibre network.

Queen's will spearhead the development of the new supercomputer and lead research, chip procurement, system architecture, advanced technology programs and the operation of the supercomputer.

Grant is quick to point out that Queen’s is not the only organization planning to submit a supercomputer proposal to the federal government.

He expects Simon Fraser University (SFU), which already has a small (compared with the world’s largest machines) supercomputer, to submit a proposal. It’s likely there’ll also be a proposal from Quebec, probably Laval University.

Also, the federally funded Digital Research Alliance of Canada has been public about soliciting sites for a large supercomputer.

The federal government, mainly through the alliance, recently invested in upgrading some of Canada’s existing supercomputers. This includes over $40 million for the “Fir” supercomputer at SFU, $21.8 million for “Nibi” machine at the University of Waterloo, and $4.25 million for AI compute infrastructure at the University of Toronto.

Grant said those supercomputers are important for general research, and such investments should continue.

However, he pointed out that none of Canada’s supercomputer are large and fast enough to complete globally in building foundational AI models or doing very large-scale computation for, for example, a jet engine, climate modelling of the entire Earth, or detailed earthquake and tsunami modelling of Vancouver.

Canada’s most recently deployed supercomputer, built by Telus, is ranked No. 78 in the world. As for publicly built supercomputers, Fir at SFU is ranked No. 87.

The speed of these types of supercomputing systems averages about 20 “petaflops,” with Canada’s top system having 22.7 petaflops. A petaflop is a unit of measure for a computer’s processing speed.

In comparison, the top supercomputing system in the world is 1,209 petaflops and those in the top 10 typically are about 250 to 300 petaflops – so orders of magnitude faster than any of Canada’s public or private supercomputers.

“Building one of those [top 10] systems is very, very different than building a system with 20 petaflops,” Grant noted.

While Canada’s comparatively small supercomputers are useful for research, those computers aren’t really meant for industry, he said. “There’s that cross-section of where you get research intersecting with industry where you get real value.”

In the innovation chain, “bridging the end of [development in] the lab to the industry store shelf is that part that we’re missing,” Grant said.

“That typically is a large supercomputer that helps translate those things where both researchers and industry can collaborate together, to get that thing out of the lab and into real production.”

It isn’t necessary to run the actual production on a large supercomputer, he added, “but it’s that last mile of the innovation pipeline that we can really enable here. And we can connect that with Canadian technologies as well.”

The goal is to build a supercomputing centre with world-calibre Canadian talent working there, who are collaborating with Canadian companies to further develop technologies and enable applications to make the entire supercomputing system a reality.

Canada has the world’s best AI designers who now need a “factory” in which to build

Granted noted that it’s best practice throughout the world for countries that have supercomputers to also to build “readiness systems.”

These are smaller, identical versions of the larger supercomputer and they’re built on different power grids for enhanced resilience.

“That’s a good idea. We probably should be deploying some ‘baby clones’ of this system throughout Canada,” he said.

That allows people in different parts of the country have physical access to the system – which he noted most actually don’t require – but it also distributes expertise regionally. So a “local” team in the West or the East or in French-speaking Quebec is trained on the system and is able to prove out applications at a smaller scale in an identical environment.

“And then when you’re ready, you jump from the readiness system to the big system and now you’ve got time to do really big stuff,” Grant said.

However, he pointed out it would be a mistake to divide the federal investment by three and build one-third the size of a supercomputer in three different places.

That wouldn’t give Canada the top-10-in-the-world supercomputer that the country needs to be a global competitor, he said.

Canada especially needs its own top-10 supercomputer now because Canadian researchers can no longer rely – given the Trump administration’s cuts to research and science – on collaborating with their U.S. colleagues to gain access to their large supercomputers.

“We can’t do that anymore. They just won’t let us on a lot of those systems,” Grant said.

U.S. tech giants like Microsoft, and potentially Google and Amazon Web Services, are expanding and building Canadian data centres and cloud capabilities while pledging to protect Canadian digital sovereignty by keeping data physically within Canada.

However, U.S. laws like the CLOUD Act could compel these companies to turn over the data to U.S. authorities, even from data centres build in Canada.

Canadian companies, to keep their training data secure and truly sovereign, need to train on a Canadian supercomputer but then, if they choose, could deploy their applications through the foreign multinationals’ clouds, Grant said.

However, there are a lot of really promising Canadian companies working on supercomputing technologies, he noted. “We’re the best designers in the world in AI, but we just don’t have the factory [the supercomputer] to actually build it.”

The federal government, with its investment, has the opportunity to build Canadian expertise into a homegrown supercomputing system, Grant said. This includes everything from designing and running the system, to figuring out how to procure the system and which components to buy, to how to troubleshot it, ensure all the technology is working properly, and keep it updated.

He compared the process of building a top-10 supercomputer to a Formula 1 racing team, where “the drivers work really closely with the engineers and the mechanics to tune that system as a whole. If you only build drivers and you don’t have the mechanics and the engineers and those two groups can’t talk to each other, you can’t have an effective racing team.”

“By having a larger centre with the right expertise and the right advanced technology program, and demonstrating these things to the world, and buying these Canadian technologies early, we can have the hope of exporting our technologies internationally,” Grant said.

“We could have a huge piece of the AI infrastructure and, more importantly, trusted AI around the world.”

Lack of supercomputing power is impairing Canada’s research and business innovation

R$

| Organizations: | |

| People: |

Ian Karlin and Ryan Grant

|

| Topics: |

Events For Leaders in

Science, Tech, Innovation, and Policy

Discuss and learn from those in the know at our virtual and in-person events.

See Upcoming Events

You have 0 free articles remaining.

Don't miss out - start your free trial today.

Start your FREE trial Already a member? Log in

By using this website, you agree to our use of cookies. We use cookies to provide you with a great experience and to help our website run effectively in accordance with our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.