Are Canadians smart enough?

Peter Josty is Executive Director of The Centre for Innovation Studies, based in Calgary.

Peter Josty is Executive Director of The Centre for Innovation Studies, based in Calgary.

"Smart enough for what?" you may ask. Canada is a small open economy in a very competitive world. The quality of the labour force – education and skill levels – is an important contributor to international competitiveness.

So we can reframe the question: does Canada’s labour force have the level of skills and knowledge necessary to compete successfully internationally?

The first topic that comes to mind is IQ. However international comparisons of IQ are a controversial field that has been criticized as being unscientific, so we will not deal with it.

There are three international comparisons with reasonably reliable methodology:

- Education levels.

- The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development's (OECD) Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) test that tests 15-year-olds on literacy and numeracy every three years. It aims to test their ability to use their reading, mathematics and science knowledge and skills to meet real-life challenges.

- The Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) is also from the OECD. This comparison has been done twice, first in 2012 and then in 2023. It aims to answer the question: Do Adults Have the Skills They Need to Thrive in a Changing World?

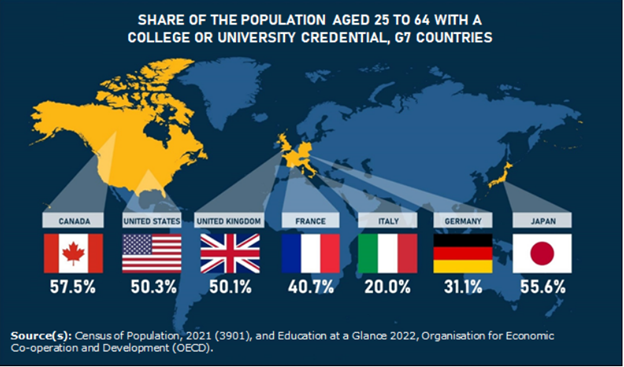

Education levels

According to Statistics Canada, Canada has the largest percentage of college or university graduates in the G7 among people aged 25-64.

Source: Statistics Canada

PISA results

The latest PISA results are shown in the table below for the three areas of mathematics, science and reading.

It is noteworthy that Canada ranks higher than its major trading partner the U.S. in each ranking. While Canada ranks #8 or #9 in each area, the U.S. ranks #34 (mathematics), #16 (science) and #9 (reading).

However, Canada’s scores have declined since well before the COVID pandemic.

The mathematics rank declined from #6 in 2006 to #9 in 2022; the reading rank fell from #2 in 2000 to #8 in 2022; and the science rank declined from #3 in 2006 to #8 in 2022.

Source: OECD

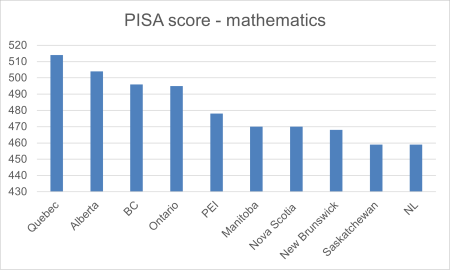

There is some regional variation across Canada. The graphic below shows the mathematics scores by province.

Source: OECD

The PISA scores need to be taken with a large grain of salt. The Canadian data was flagged: “One or more PISA sampling standards were not met.”

Some countries are reported to put forward only their best schools; it measures a very narrow range of skills and its statistical reliability is uncertain.

Nevertheless, the fact that absolute marks declined by around five percent over the last 20 years is not good news.

PIAAC results

This is based on a survey of almost 12,000 adults aged 16-65 conducted by Statistics Canada face-to-face in the person’s home, so from a methodology point of view it is much more robust than the PISA results.

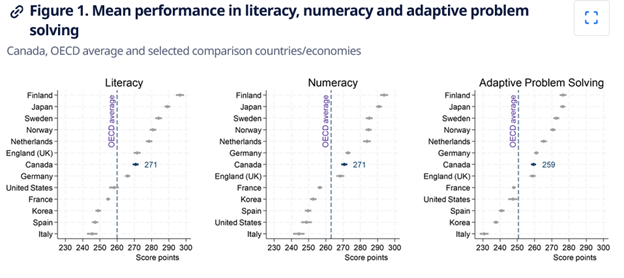

PIAAC is part of a large OECD international study that includes 31countries. The skills are rated on a five-point scale with five being best. It addresses performance in literacy, numeracy and adaptive problem solving.

The graphic below summarizes the Canadian results compared with selected countries. Canada’s score is 271 for both literacy and numeracy performance and 259 for adaptive problem solving.

Source: Statistics Canada, OECD

The results from the 2023 survey shows Canada at just above the OECD average. There are some interesting findings from the survey:

- Higher education qualifications do not necessarily lead to higher skills proficiency.

- Higher numeracy scores lead to better health, earnings, life satisfaction, trust and volunteer activities.

- Significant segments of the Canadian population score at Level 1 or below on a five-point (five levels) scale: 18 percent in literacy, 19 percent in numeracy, and 22 percent for adaptive problem solving.

- However, Canada fares much better than the U.S. where much larger segments of the population score at Level 1 or below: 28 percent in literacy, 34 percent in numeracy and 32 percent in adaptive problem solving.

- Scores for literacy, numeracy and adaptive problem-solving peak in the 25-34 age group and decline slowly for older age groups.

- Labour force participation is much higher among those with Level 4 or above skills (94 percent) compared with Level 1 or below skills (67 percent).

Conclusion

Of the three data sources used, the PIAAC results are the most robust and best indicative of real-world situations.

By these measures Canada ranks just above the OECD average, well behind countries such as Finland, Japan, Sweden, Norway, and the Netherlands.

Canada performs better than the U.S. on all three measures. This is not a particularly reassuring result, particularly as PISA scores (which may be an early indicator of future PIAAC scores) have been declining for almost two decades.

One-fifth of the Canadian population has skills at Level 1 or below, which limits their employability. Only two thirds of this group are in the labour force.

The high level of people with college or university credentials is good, but its impact may be limited due to the finding from the PIAAC study that higher education qualifications do not necessarily lead to higher skills proficiency.

The bottom line is that a focus on population skill levels should be a much more important part of Canada’s growth and productivity agenda.

R$

| Organizations: | |

| People: | |

| Topics: |

Events For Leaders in

Science, Tech, Innovation, and Policy

Discuss and learn from those in the know at our virtual and in-person events.

See Upcoming Events

You have 0 free articles remaining.

Don't miss out - start your free trial today.

Start your FREE trial Already a member? Log in

By using this website, you agree to our use of cookies. We use cookies to provide you with a great experience and to help our website run effectively in accordance with our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.